The Balance Sheet

Home > Functions > Finance > Accounting > Financial > Balance Sheet

Welcome to the Balance Sheet

When it comes to financial management or just business in general a fundamental phrase that comes up is ‘what does the balance sheet look like?’ and this is an excellent question as the balance sheet of business not only shows how much the business is worth at a point in time but also the size, strength and even personality of the business. When someone sees a balance sheet of your business what they are looking at is you in the past but also in the future. Let’s walk through what the balance sheet is, why it is so fundamental to a business, and how you can use it as both a financial report but also as a vision to how you want your business to be and the world that it lives in.

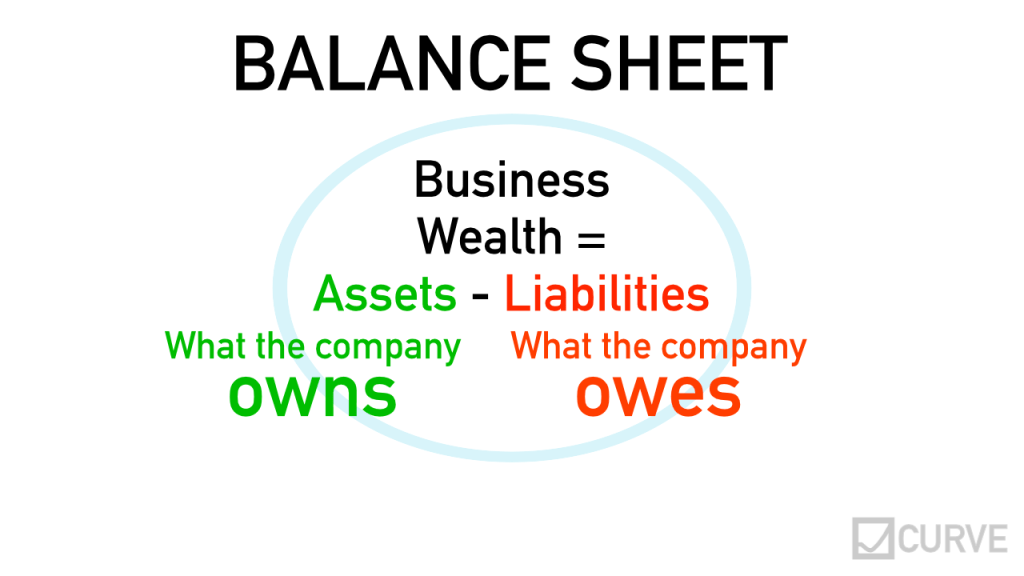

What is a balance sheet?

A balance sheet shows how much a business is worth by showing how much worth it has in assets against how much it owns in claims to other businesses and shareholders. This is the why it’s called a balance sheet – the assets (what the common owns of value) always equals the money that the business owns in claims to others. The reason why it must equal is that the business is not real in the sense that it can own anything; all its value belongs to a human being (or another business – it gets very complicated so let’s move on) who will use that money for their lives.

You will never find a balance sheet where the assets don’t equal the claims where claims are money owned to others plus shareholder equity aka the excess.

Assets balance against Claims

Assets = Claims

The business owns nothing

Business owners own everything

Assets

Assets are things or resources that a business use to generate wealth through it’s business activities. There are many types of asset type but the simplest and most common are cash and inventory with cash buying things (inventory) to sell which in turns generates more cash.

Many businesses only have these two types of assets as they are needed for the simplest and most fundamental business – buy stuff, sell stuff.

Before getting into the complexity of different types of assets we need to define what an asset is (cash and inventory are obvious). These are the guidelines for what an asset is.

- Possible future financial benefit

The thing you are calling an asset must be able to generate wealth for the business or already hold a monetary value. Some assets over time can appreciate like a building but most lose value over time or depreciate. Once the asset has no value then it has to be be removed from the business’s assets. The valuation of an asset like the rest of the accounts have to be true and fair which means stating honestly what you think the asset is worth. If an authority or another stakeholder asks how that figure was reached there should be a justification as to how those numbers where reached. The reason why these numbers need to be true and fair is many businesses borrow one based on the businesses assets (this is mainly for company or incorporated businesses) with the asset used as a security against a default against payment. This is why it’s easy to get credit as a large business than a small one even if they produce the small level of return.

- The business must own or have an exclusive right of the asset or can control the benefit generated

This might seem obvious that a business bought and paid for the asset that they are claiming for e.g. a car or machine. This is true for a lot of assets but there are examples where the asset is owned by one business but used by another. There are also circumstances where a business is cheeky and claims exclusive use but they do not control the asset. Logistics are good examples where a business has access to a particular road or channel and highlights this as something of value. Whilst the business may be lucky enough to have access unless they can stop others from using is it does not fall into their assets. However, they can make these claims in business statements like ‘with exclusive rights to road A …’ but they can’t claim that road as an asset. - The benefit must arise from a past transaction or event

This relates to point 2 – the business need to actual own and control the benefit from something that has happened not something that will happen even if it’s absolutely certain. This normally means that benefit has been paid for in a monetary exchange. This strictly means that a business may already be using a tool and has been told that it can keep it but it can’t claim it as an asset – there needs to be formal and recognised transaction to own the benefit for it become an asset. Think of it like when someone lends you something and they say you can keep it but you don’t have the receipt so they could come back and claim it. In financial accounting the devil is in the recorded detail as talk is expensive. - The benefit of the asset must be capable of being measured in monetary terms

All assets are assessed to be valuable in terms of money, nothing else regardless of how unfair or difficult that may be. The importance of measuring the benefit of an asset in money terms is that it allows assets and liabilities to be added and subtracted. If we used another measurement it would be impossible. This can lead to some tricky questions and logic: what is a brand worth? Is a person an asset? If so can a person be a liability?

All four rules must apply and fairly. No squinting to try and get something to be an asset when it’s not. No cheating as it will only lead to pain.

Once identified assets can be divided into different types to help the reader see how the total assets break down to support the generation of wealth. The division can be done in two main ways: 1) physicality and 2) time.

Tangible Assets – “touchable”

Assets that have physical properties and affected by the laws of the universe e.g. gravity, heat etc are called Tangible assets meaning ‘perceptible by touch’. Tangible assets make up the majority of a businesses wealth in industries that make physical things. A factory will have machinery that would be a tangible asset (assuming they can define it by the four rules above.

As tangible assets have physical properties and their value is in they manipulating or transferring other physical things they lose value through wear and through better alternatives being available. This reduction in value for tangible assets is called depreciation an accounting activity that rationally reduces the value of a tangible asset over a set period of time.

For example if you bought an oven to bake bread for £1,000. An oven is definitely a physical thing that creates value, owned exclusively by you and can be measured in cash terms. Every time you use the oven there is a little wear on it – this reduces the value a little. Over a year it will reduce it more and so we have to recognise this in the accounts by reducing its value. Over the year a more efficient oven enters the market that is better and costs £1,000. This alternative also reduces the value of the oven and needs to be taken into consideration. To make things simple we just reduce the oven’s value in monetary terms over its economic life which is the life in which it’s seen as being useful to generate wealth. We could 100 years to retain the value of the asset in the balance sheet for longer however there are principles and guidelines on how to depreciate tangible assets so it’s more likely to be 5. The oven could still have value but this would be called out a residual value or even scrap to show that the metal itself could be sold to generate cash if the business wanted.

Intangible Assets – “untouchable”

If tangible are assets you can feel everything else is an intangible asset. More specifically under the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) an intangible asset is:

- Identifiable – a thing you can point out and say ‘that non- real thing is valuable’. This identification may seem easy but trying to separate out a specific non-real thing is totally in the eye of the definer. One way of check if it is an intangible is to able to answer the question: “would someone be able to buy it and use themselves?” if the answer is “yes” then, like tangible assets, it can be a intangible asset. If the answer is “well maybe” then it probably isn’t. Branding is a good example of this – the value is not just in one brand but other intangible parts of the brand. Once identified then the non-real thing needs to become

- Non-monetary – not based on money. A business can have an asset that is not tangible or intangible as it’s based on a somethings inbetween namely another business. A business that owns an income from another business can claim this is a financial asset, which is an asset you can’t touch but is not, strictly an intangible asset. Confused? Don’t worry – just note that the intangible asset must not be linked to something of monetary value.

- Without physical substance – as discussed the intangible asset can not be tangible.

Now that we have defined what an intangible asset the next questions is why and how are they valued?

With assets in general we need to show how the business makes money with the things it controls and show in a fair and truthful way that we are decreasing the value of those assets as they are used fairly either via depreciation if a tangible asset or amortisation if an intangible asset. From an accounting point of view it’s also quite straight forward: cash is paid out to buy the asset giving it’s starting valuation which then reduces over time. We could do the same with an intangible asset that we buy. But what about an asset tangible or intangible that we don’t buy but we make ourselves? We are spending money out but we are building and asset that has value. To recognise and recover this transaction the expense is capitalised.

Capitalisation

Cap, Capital, and Capitalisation are routed in the Latin caput meaning head or connected to the head, or top position. Anything that involves “cap” means to make important so people can see that it’s important. This is exactly what happens when something a business has made wants the value of that recognised – the work is capitalised turning money spent creating something into an asset worth something in the same way that a person is made a captain or a location is made a capital (and vice-versa: decapitation is the removal of the head).

There are strict rules for capitalisation to prevent incorrect definition of the asset and plumping up the balance sheet. There are you main types of capitalisation: 1) tangible assets and, 2) intangible assets. Tangible assets like property, plant, equipment (PPE) that are made can be reasonably easily valued and defined by the four rules stated above as building or a machine can be valued as if bought externally. Intangible assets is more difficult as the value is tricky to evaluate. What can be done quite easily is to look to recover the cost of creating the intangible asset rather than try and define a market value. For example if it cost £10,000 to register a trademark this could be capitalised. Computer software can also be capitalised with regard to the cost of creating it. In the case of software once capitalised it is amortised like a tangible asset as it becomes less valuable with time due to the features not being as valuable.

Current Assets

Non-current Assets

Claims

Liabilities